A couple of weeks ago it was international cheese day, so I figured, let´s take a look at some painted cheese. I´m as Dutch as a Gouda cheese, so it´s not a surprise I love the actual product as well, not just the painted ones. A few pieces of cheese, some bread, a glass of wine… and I´m in. Any day is good to do a little cheese tasting.

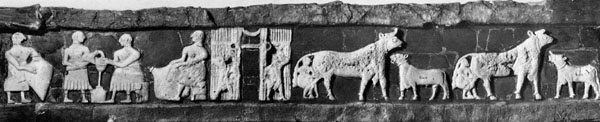

But getting back to the images, there are quite some examples of cheese on murals, paintings, etc. One of the oldest is the dairy frieze from the third millennium BC, where the production of cheese is shown as if it were a comic strip. Already in this period there was a love for cheese, which is no surprise to me.

If we now get a little closer to more known examples, something struck my attention. On some Dutch still lifes, cheese has a prominent place. Sometimes they are placed on top of each other, giving the stack a considerable volume within the painting. As a cheese lover, they catch my attention instantly. But then, I look a little bit closer, and they don´t look very attractive, I have to admit, the pour things are not so good looking.

Some have stains or even cracks filled with mold, and I don´t mean the mold on cheese after ripening, like on soft matured cheeses for example, but the one that appears when everybody forgets that it still exists and the poor thing turns green.

I imagine it all has to do with the production process that wasn´t anything like it is today, nor were the options to preserve it obviously. Even the biological process of fermentation was still unknown, and made it impossible to better understand the production process like nowadays. But then again, aren´t they delicious? Especially the raw milk varieties. We love them anyway, even if they are not that good looking.

In this work from the Dutch painter Floris Claesz. van Dijk we see a couple of these stacked cheeses. I wonder what type of cheese they were, when they were eaten and what they were used for, don´t you? The smallest one on top, has an ash grey colour which doesn´t ring a bell, and it looks so dry that the only purpose it seems to have is to be grated. It owes its dark green colour to herbs like parsley, which was normally added to give low-fat cheeses more flavour. Don´t we buy cheeses with nettle, chives or even pesto nowadays? This green cheese is still very common.

When we speak in terms of it´s use, this type of cheese could have indeed be used for grating. If we look up Magirus´ recipe book (which I introduced in my piece on the royal tart), published a few years before this painting was made, we can find 28 references to ´g(h)eraspten kese´, or indeed: grated cheese.

Taking a closer look into this book, we can see that the word cheese appears no less than 64 times, and with a few variations as well. An incredible number of times, uncommon for contemporary Dutch recipe books. This is where the influence of Bartolomeo Scappi´s Italian kitchen becomes evident, from whom Magirus borrowed quite some recipes for his book. What Magirus does is accommodate them to the already famous and abundant cheese in the Low Countries.

If we now go back to the painting and compare the three cheeses with the varieties in the book, each of the painted ones can be connected to one of the categories he mentiones. From top to bottom we have the ´drooghen kese´ or dry cheese, ´ouden kese´ or ´old cheese´ and finally ´nieuwen Hollandschen kese´ or new Dutch cheese. Magirus names quite defined and common varieties so it seems. In his recipes he mentiones all these types of cheeses as an ingredient in various dishes, especially for tarts and pies: fillings with meat, offal, or mushrooms and vegetables, even with fruit and nuts. Cheese also went into stuffings for roasted poultry or other meats.

And the cheese was of course served as is, at the end of a meal. According to several medical contemporary treatises, the best for this purpose were hard cheeses, as they would serve to close the stomach. Bitter and sour fruit, nuts and olives also did the trick. The combination of these ingredients, except for slight variations, can be seen on this painting by Van Dijck, just like on some other paintings from around that period, such as these from Pieter Claesz or Clara Peeters. They could all be representing the mentioned last course of a meal, finishing the banquet properly and with the right products.

But wait, there is more to these cheeses. Magirus doesn´t only tell us how to cook with them, or when to serve them, he also gives advice on what to serve depending on which dinner guest one had:

Want meest alle vrouwen met soeticheyt, de mans met suer, met sout, met sterck ende met bitter te onderhouden syn.

And translated:

Because most woman are taken care of with sweets, and men with sour, salted, strong and bitter.

And that´s that. Equality? That was certainly not an issue yet. Well, I tell you one thing, Magirus, I prefer a plate of the ´sour, salted, strong and bitter´, please. He recommends a good Parmesan and Dutch cheese, but also anchovies, dried salmon, seasoned oysters, nuts, dried fruit and wine, just to name a few. Nothing wrong with that, don´t you think? Let´s leave these masculine and feminine last courses for another day, there´s still a lot to talk about.

So, what about a nice cheese plate, to close our stomach? Don´t forget the hard cheese, or any other type you like of course.

References:

Bruyn, J. Dutch cheese: a problem of interpretation. Simiolus (24), 1996.

Kwak, Z. ‘Proeft de kost en kauwtse met uw’ oogen’. Beeldtraditie, betekenis en functie van het Noord-Nederlandse keukentafereel (ca. 1590-1650). Tesis doctoral. Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2014.

El arte de Clara Peeters [catálogo exposición]. Amberes: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten/ Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2016.

Smakelijk eten: eten en drinken in de Gouden Eeuw [catálogo exposición]. Hoorn: Westfries Museum, 2011.

Transcription of Magirus´ recipe book (in Dutch): http://www.kookhistorie.nl/